Angular resolution

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2012) |

Angular resolution describes the ability of any image-forming device such as an optical or radio telescope, a microscope, a camera, or an eye, to distinguish small details of an object, thereby making it a major determinant of image resolution. It is used in optics applied to light waves, in antenna theory applied to radio waves, and in acoustics applied to sound waves. The colloquial use of the term "resolution" sometimes causes confusion; when an optical system is said to have a high resolution or high angular resolution, it means that the perceived distance, or actual angular distance, between resolved neighboring objects is small. The value that quantifies this property, θ, which is given by the Rayleigh criterion, is low for a system with a high resolution. The closely related term spatial resolution refers to the precision of a measurement with respect to space, which is directly connected to angular resolution in imaging instruments. The Rayleigh criterion shows that the minimum angular spread that can be resolved by an image-forming system is limited by diffraction to the ratio of the wavelength of the waves to the aperture width. For this reason, high-resolution imaging systems such as astronomical telescopes, long distance telephoto camera lenses and radio telescopes have large apertures.

Definition of terms

[edit]Resolving power is the ability of an imaging device to separate (i.e., to see as distinct) points of an object that are located at a small angular distance or it is the power of an optical instrument to separate far away objects, that are close together, into individual images. The term resolution or minimum resolvable distance is the minimum distance between distinguishable objects in an image, although the term is loosely used by many users of microscopes and telescopes to describe resolving power. As explained below, diffraction-limited resolution is defined by the Rayleigh criterion as the angular separation of two point sources when the maximum of each source lies in the first minimum of the diffraction pattern (Airy disk) of the other. In scientific analysis, in general, the term "resolution" is used to describe the precision with which any instrument measures and records (in an image or spectrum) any variable in the specimen or sample under study.

The Rayleigh criterion

[edit]

The imaging system's resolution can be limited either by aberration or by diffraction causing blurring of the image. These two phenomena have different origins and are unrelated. Aberrations can be explained by geometrical optics and can in principle be solved by increasing the optical quality of the system. On the other hand, diffraction comes from the wave nature of light and is determined by the finite aperture of the optical elements. The lens' circular aperture is analogous to a two-dimensional version of the single-slit experiment. Light passing through the lens interferes with itself creating a ring-shape diffraction pattern, known as the Airy pattern, if the wavefront of the transmitted light is taken to be spherical or plane over the exit aperture.

The interplay between diffraction and aberration can be characterised by the point spread function (PSF). The narrower the aperture of a lens the more likely the PSF is dominated by diffraction. In that case, the angular resolution of an optical system can be estimated (from the diameter of the aperture and the wavelength of the light) by the Rayleigh criterion defined by Lord Rayleigh: two point sources are regarded as just resolved when the principal diffraction maximum (center) of the Airy disk of one image coincides with the first minimum of the Airy disk of the other,[1][2] as shown in the accompanying photos. (In the bottom photo on the right that shows the Rayleigh criterion limit, the central maximum of one point source might look as though it lies outside the first minimum of the other, but examination with a ruler verifies that the two do intersect.) If the distance is greater, the two points are well resolved and if it is smaller, they are regarded as not resolved. Rayleigh defended this criterion on sources of equal strength.[2]

Considering diffraction through a circular aperture, this translates into:

where θ is the angular resolution (radians), λ is the wavelength of light, and D is the diameter of the lens' aperture. The factor 1.22 is derived from a calculation of the position of the first dark circular ring surrounding the central Airy disc of the diffraction pattern. This number is more precisely 1.21966989... (OEIS: A245461), the first zero of the order-one Bessel function of the first kind divided by π.

The formal Rayleigh criterion is close to the empirical resolution limit found earlier by the English astronomer W. R. Dawes, who tested human observers on close binary stars of equal brightness. The result, θ = 4.56/D, with D in inches and θ in arcseconds, is slightly narrower than calculated with the Rayleigh criterion. A calculation using Airy discs as point spread function shows that at Dawes' limit there is a 5% dip between the two maxima, whereas at Rayleigh's criterion there is a 26.3% dip.[3] Modern image processing techniques including deconvolution of the point spread function allow resolution of binaries with even less angular separation.

Using a small-angle approximation, the angular resolution may be converted into a spatial resolution, Δℓ, by multiplication of the angle (in radians) with the distance to the object. For a microscope, that distance is close to the focal length f of the objective. For this case, the Rayleigh criterion reads:

- .

This is the radius, in the imaging plane, of the smallest spot to which a collimated beam of light can be focused, which also corresponds to the size of the smallest object that the lens can resolve.[4] The size is proportional to wavelength, λ, and thus, for example, blue light can be focused to a smaller spot than red light. If the lens is focusing a beam of light with a finite extent (e.g., a laser beam), the value of D corresponds to the diameter of the light beam, not the lens.[Note 1] Since the spatial resolution is inversely proportional to D, this leads to the slightly surprising result that a wide beam of light may be focused on a smaller spot than a narrow one. This result is related to the Fourier properties of a lens.

A similar result holds for a small sensor imaging a subject at infinity: The angular resolution can be converted to a spatial resolution on the sensor by using f as the distance to the image sensor; this relates the spatial resolution of the image to the f-number, f/#:

- .

Since this is the radius of the Airy disk, the resolution is better estimated by the diameter,

Specific cases

[edit]

Single telescope

[edit]Point-like sources separated by an angle smaller than the angular resolution cannot be resolved. A single optical telescope may have an angular resolution less than one arcsecond, but astronomical seeing and other atmospheric effects make attaining this very hard.

The angular resolution R of a telescope can usually be approximated by

where λ is the wavelength of the observed radiation, and D is the diameter of the telescope's objective. The resulting R is in radians. For example, in the case of yellow light with a wavelength of 580 nm, for a resolution of 0.1 arc second, we need D=1.2 m. Sources larger than the angular resolution are called extended sources or diffuse sources, and smaller sources are called point sources.

This formula, for light with a wavelength of about 562 nm, is also called the Dawes' limit.

Telescope array

[edit]The highest angular resolutions for telescopes can be achieved by arrays of telescopes called astronomical interferometers: These instruments can achieve angular resolutions of 0.001 arcsecond at optical wavelengths, and much higher resolutions at x-ray wavelengths. In order to perform aperture synthesis imaging, a large number of telescopes are required laid out in a 2-dimensional arrangement with a dimensional precision better than a fraction (0.25x) of the required image resolution.

The angular resolution R of an interferometer array can usually be approximated by

where λ is the wavelength of the observed radiation, and B is the length of the maximum physical separation of the telescopes in the array, called the baseline. The resulting R is in radians. Sources larger than the angular resolution are called extended sources or diffuse sources, and smaller sources are called point sources.

For example, in order to form an image in yellow light with a wavelength of 580 nm, for a resolution of 1 milli-arcsecond, we need telescopes laid out in an array that is 120 m × 120 m with a dimensional precision better than 145 nm.

Microscope

[edit]The resolution R (here measured as a distance, not to be confused with the angular resolution of a previous subsection) depends on the angular aperture :[5]

- where .

Here NA is the numerical aperture, is half the included angle of the lens, which depends on the diameter of the lens and its focal length, is the refractive index of the medium between the lens and the specimen, and is the wavelength of light illuminating or emanating from (in the case of fluorescence microscopy) the sample.

It follows that the NAs of both the objective and the condenser should be as high as possible for maximum resolution. In the case that both NAs are the same, the equation may be reduced to:

The practical limit for is about 70°. In a dry objective or condenser, this gives a maximum NA of 0.95. In a high-resolution oil immersion lens, the maximum NA is typically 1.45, when using immersion oil with a refractive index of 1.52. Due to these limitations, the resolution limit of a light microscope using visible light is about 200 nm. Given that the shortest wavelength of visible light is violet (),

which is near 200 nm.

Oil immersion objectives can have practical difficulties due to their shallow depth of field and extremely short working distance, which calls for the use of very thin (0.17 mm) cover slips, or, in an inverted microscope, thin glass-bottomed Petri dishes.

However, resolution below this theoretical limit can be achieved using super-resolution microscopy. These include optical near-fields (Near-field scanning optical microscope) or a diffraction technique called 4Pi STED microscopy. Objects as small as 30 nm have been resolved with both techniques.[6][7] In addition to this Photoactivated localization microscopy can resolve structures of that size, but is also able to give information in z-direction (3D).

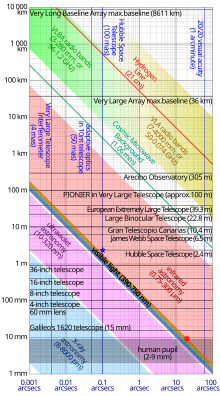

List of telescopes and arrays by angular resolution

[edit]| Name | Image | Angular resolution (arc seconds) | Wavelength | Type | Site | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global mm-VLBI Array (successor to the Coordinated Millimeter VLBI Array) | 0.000012 (12 μas) | radio (at 1.3 cm) | very long baseline interferometry array of different radio telescopes | a range of locations on Earth and in space[8] | 2002 - | |

| Very Large Telescope/PIONIER | 0.001 (1 mas) | light (1-2 micrometre)[9] | largest optical array of 4 reflecting telescopes | Paranal Observatory, Antofagasta Region, Chile | 2002/2010 - | |

| Hubble Space Telescope |  |

0.04 | light (near 500 nm)[10] | space telescope | Earth orbit | 1990 - |

| James Webb Space Telescope | 0.1[11] | infrared (at 2000 nm)[12] | space telescope | Sun–Earth L2 | 2022 - |

See also

[edit]- Angular diameter

- Beam diameter

- Dawes' limit

- Diffraction-limited system

- Ground sample distance

- Image resolution

- Optical resolution

- Sparrow's resolution limit

- Visual acuity

Notes

[edit]- ^ In the case of laser beams, a Gaussian Optics analysis is more appropriate than the Rayleigh criterion, and may reveal a smaller diffraction-limited spot size than that indicated by the formula above.

References

[edit]- ^ Born, M.; Wolf, E. (1999). Principles of Optics. Cambridge University Press. p. 461. ISBN 0-521-64222-1.

- ^ a b Lord Rayleigh, F.R.S. (1879). "Investigations in optics, with special reference to the spectroscope". Philosophical Magazine. 5. 8 (49): 261–274. doi:10.1080/14786447908639684.

- ^ Michalet, X. (2006). "Using photon statistics to boost microscopy resolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (13): 4797–4798. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.4797M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0600808103. PMC 1458746. PMID 16549771.

- ^ "Diffraction: Fraunhofer Diffraction at a Circular Aperture" (PDF). Melles Griot Optics Guide. Melles Griot. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-08. Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- ^ Davidson, M. W. "Resolution". Nikon’s MicroscopyU. Nikon. Retrieved 2017-02-01.

- ^ Pohl, D. W.; Denk, W.; Lanz, M. (1984). "Optical stethoscopy: Image recording with resolution λ/20". Applied Physics Letters. 44 (7): 651. Bibcode:1984ApPhL..44..651P. doi:10.1063/1.94865.

- ^ Dyba, M. "4Pi-STED-Microscopy..." Max Planck Society, Department of NanoBiophotonics. Retrieved 2017-02-01.

- ^ "Images at the Highest Angular Resolution in Astronomy". Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy. 2022-05-13. Retrieved 2022-09-26.

- ^ de Zeeuw, Tim (2017). "Reaching New Heights in Astronomy - ESO Long Term Perspectives". The Messenger. 166: 2. arXiv:1701.01249. Bibcode:2016Msngr.166....2D.

- ^ "Hubble Space Telescope". NASA. 2007-04-09. Retrieved 2022-09-27.

- ^ Dalcanton, Julianne; Seager, Sara; Aigrain, Suzanne; Battel, Steve; Brandt, Niel; Conroy, Charlie; Feinberg, Lee; Gezari, Suvi; Guyon, Olivier; Harris, Walt; Hirata, Chris; Mather, John; Postman, Marc; Redding, Dave; Schiminovich, David; Stahl, H. Philip; Tumlinson, Jason (2015). "From Cosmic Birth to Living Earths: The Future of UVOIR Space Astronomy". arXiv:1507.04779 [astro-ph.IM].

- ^ "FAQ Full General Public Webb Telescope/NASA". jwst.nasa.gov. 2002-09-10. Retrieved 2022-09-27.

External links

[edit]- "Concepts and Formulas in Microscopy: Resolution" by Michael W. Davidson, Nikon MicroscopyU (website).